You are viewing the expanded version of this Harbour,

for faster browsing

use the regular version here

Medway 1, Entrance, Creeks and Anchorages up to Gillingham Reach

Courtesy Flag

Flag, Red EnsignWaypoint

From the W. Nore Swatch R.Buoy: 51:28'.3 N 000:45'.55 E From the E. No.5 G.Buoy 51:28'.1 N 000:48'.5 E Position Approx.Charts

Admiralty, 1834, SC5606Rules & Regulations

A 6 knot speed limit operates west of Folly Point on Hoo Island. Monitor VHF Ch 74 and 16

Hazards

Explosive Laden Wreck in the Approach, Overfalls near Sheerness Fort on the Ebb.Tidal Data Times & Range

HW Dover +0130 at Sheerness, HW Dover +0140 Chatham. Data at Sheerness..MHWS 5.8m MHWN 4.7m, MLWN 1.5m, MLWS 0.6m (links)This site is designed for slower, roaming broadband connections, like you would get at sea, so it needs JavaScript enabled to expand the text.

General Description

Contact Medway VTS 01795 596596 VHF #74

The River Medway is a historic waterway much associated with the Navy....

.... and stretches inland from the entrance at Sheerness some 13 miles to Rochester. At this point it is bridged and masted vessels will find their progress blocked. Motor vessels and small craft can continue up the Medway to Allington lock. From here it is possible to navigate as far as Maidstone.

The Medway comes under the governance of Peel Ports from Liverpool

Huge ships use the entrance at Sheerness, Sheerness docks, the Liquid Natural Gas terminal, and the container facilities at Thamesport. These shipping facilities are all within the first few miles of the entrance.

Once clear of these, large (but not huge) shipping can still be encountered all the way up to Rochester. There is however quite a large expanse of water and it's not too much trouble to keep out of their way.

The industrial and shipping facilities lie on the Northern bank once within the Medway. The Southern side is given over to deserted creeks and saltings, some of which have deepwater and many of which dry.

Once further in towards Gillingham Reach, river narrows down and facilities for the leisure boater increase, with several mooring options including clubs, marinas and boatyards. The towns of Gillingham, Chatham and Rochester line the river in this area, while several smaller villages such as Hoo and Upnor hug the riverbank too.

If you can fit under the bridge at Rochester several more mooring options are available a little further up stream.

It is proposed to cover the River Medway in three sections.

1. Medway 1, Entrance to Gillingham Reach, including the Creeks and Anchorages.

2. Medway 2, Gillingham Reach to Rochester Bridge, inc the Marinas

This article deals with the first section, the entry to the Medway via Sheerness, the passage up the Medway as far as Gillingham Reach, and the creeks and anchorages on the southern side. The entry to the River Swale and facilities at Queenborough are covered in a separate article..... Queenborough is the closest place with yachting facilities to the entrance of the Medway.

This section of Medway offers a wide expanse of fairly smooth water and is very popular with yachtsman. For those looking for anchorages far from civilisation this area has plenty to offer, although the view is somewhat dominated by the industrial scenery on the North bank. The creeks and anchorages are a long way from any facilities whatsoever, with little or no chance of nipping ashore for provisions. At weekends in the summer they can get very crowded with yachts, but weekdays and off-season you're probably have the whole place to yourself.

The area covered is home to a couple of clubs and a couple of boatyards, one of which specialises in laying up ashore and DIY fit outs.

Approach

Ships approaching the River Medway tend to come up the Thames Estuary using the Princes Channel.....

....and then make their approach via the dredged and buoyed channel leading into Sheerness. There is no need for pleasure craft to use this channel as there is plenty of water on either side of it.

The tall chimney which was on the West side of the entrance at the Grain Power Station is no more.

The eastern side is marked by Garrison Point and the Port of Sheerness. The port control office sits atop the large fort, and displays a bright light (Fl.7s) to warn of shipping movements. The light is directed to seawards if shipping is leaving the Medway, and directed inwards if shipping is approaching the Medway.

Pilotage details:

The harbour authorities here can be contacted on VHF channel 74, callsign "Medway VTS". Their phone number is 01795 596596 and we provide a link to their website below:

Be advised that that telephone number is answered in Sheerness and the radio Channel in Liverpool

Small craft are recommended to use the track shown on the chart which keeps them to the North West of the main channel and out of harms way.

If approaching from the East it is easy to keep it out of the Medway Approach Channel by skirting it on the northern side. Keeping just outside the line of green conical buoys by leaving them on your port hand side will bring you inwards and past the wreck of the Richard Montgomery. This is a no go area, with the masts visible much of the time. It is well marked by yellow buoys, and you should leave these close to starboard.

Continuing on this approach will take you past the Green buoys No. 9 (Fl.G.5s) and No. 11 (Fl(3)G.10s) from where you can make the recommended approach.

If coming from the West, or perhaps from across the Thames estuary you could make for the red can Nore Swatch buoy (Fl(4)R.15s). A generally southerly course from here will bring you to the unlit green Grain Edge buoy or the Green No. 11 buoy already mentioned. Due allowance should be made for the tide which could be pushing you towards Grain Spit, or towards the wreck. From this area the recommended approach can again be tackled.

From the number 11 Green Buoy a generally south westerly course is steered towards the green Grain Hard Buoy (Fl.G.5s) and then SSW towards the North Kent green conical buoy (Q.G). It's important not to stray to starboard as the bank here is very steep too.

Large shipping moving through this area is normally accompanied by tugs and it's best to keep well out of the way.

As you traverse this area you will see Sheerness Docks on the eastern side, and the entrance to the Swale. If making for Queenborough you can cross over if the coast is clear long before you reach the N.Kent buoy. Make for the easterly cardinal Queenborough Spit Buoy (Q(3)10s) and be sure to leave it on your starboard side.

Continuing up the Medway is straightforward enough now with plenty of deep water around industrial facilities on your starboard side. The first you come across is the liquid natural gas terminal that handles very large brightly painted ships, the second is Thamesport, a container dock... which also handles very large ships. On the southern side of the River opposite the LNG terminal there are heavy mooring buoys and these Mark the southern edge of the deepwater.

The entrance to Stangate Creek is marked by an easterly Cardinal buoy, Stangate Spit (VQ(3)5s) and comes up on the southern side just after the above-mentioned mooring buoys. Entrance to the Creek is made by leaving this Cardinal buoy on your starboard side as you head south into the creek. The delights of the creeks are described shortly.

If continuing westwards towards Gillingham and Rochester you can take advantage of the Sharpness Shelf to keep completely out of the way of shipping. There is plenty of water here for pleasure craft. From a point just north of the Stangate Spit buoy steer a generally westerly course with a touch of North, leaving the red buoyage marking the shipping channel well off on your starboard side. On your port side is Burntwick Island which should be given reasonable offing.

As you approach the red can buoy No. 14 (Fl.R.5s) the River bends to the south-west into Kethole Reach. A line of heavy mooring buoys on the south-east side define the edge of the channel, but small craft can keep inside of these. Half acre Creek branches off to the South at the end of this line of buoyage, and is described later.

For the main channel you'll first come across the E Bulwark conical buoy marking an historical wreck (with an accompanying unlit red can buoy to the west of the wreck); this is followed by the Bees Ness Jetty and then by Oakham Ness Jetty protruding deep into the River,(emanating from the Northwestern bank) and lying to the South of this the red can buoy Bishop, No. 16 (Fl(2)R.10s). This red buoy marks Bishops Spit and needs to be left on your port side.

The River now follows a westerly course in Long Reach, well marked on each side with a red and green buoyage. The Jetty projecting into the River from Kingsnorth power station (which is no more - it's been completely raised to the ground) will clearly be seen ahead. It will be necessary to use the main channel now. Once past Kingsnorth Jetty on your starboard side and Darnett Ness on your port side, which is very conspicuous with it's fort, the channel swings to the Southwest into Pinup Reach. Hoo Island with it's fort will be seen on your starboard hand. A matching pair of buoys, the red can number 24 (Fl.R.5s) and the green conical buoy Folly, No. 25 (Fl(3)G.10s) will be seen, simply pass between them into Gillingham Reach.

From here onwards to Rochester Bridge is covered in a separate article. (HERE)

It is not necessary when negotiating the River to keep out of the deep channel, and it is a relatively simple matter to follow the buoyage straight in from Sheerness onwards during the day. At night although it is all well lit, it is far from straightforward...I know ! The background lights and the sheer quantity of lit buoyage are confusing to the max. Even if you've been up and down the river in daylight many many times, at night things are totally different. Add to that the number of unmarked and unlit heavy mooring buoys that you could have an unpleasant encounter with, make a night-time entry inadvisable. Note that the channel passing to the South of the Isle of Grain has no PHM between the S.Kent buoy (off Queensborough) and the No 12 buoy (off Elphinstone Point) but there are two Cardinal Marks off Stangate Spit and two Bad Ground markers - all four flashing combinations of white light. The north side of that channel is very clear being floodlit with green lights of some sort or the other on the dolphins.

If you do have to come in at night it would probably be a good idea to enter a large series of waypoints into your GPS and follow them, whilst ticking off the buoyage as you pass it. (Remember Timothy Spalding in his barge in the "All at Sea" series - got lost in here at night and ended up having to call out the Lifeboat which found him somewhere up Stangate Creek!!)

Berthing, Mooring & Anchoring

For the yachtsman or motorboater, entry to the Medway also leads to Queenborough.

Otherwise in the section described it's out with old "cold-nose", and anchor. Possible spots are now described where you may lay afloat. For those able to take the ground opportunities abound. Or you can pass quickly through on your way to the fleshpots of Gillingham, Chatham and Rochester !

Stangate Creek and Sharfleet Creek are popular anchorages in this area, where small craft can lie afloat at all states of the tide and obtain some shelter from the surrounding marshlands.

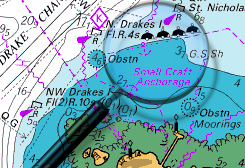

The entry point to Stangate Creek is marked by the easterly cardinal buoy Stangate Spit, and the arrangement is best seen by reference to the chart. A generally southerly heading keeps you in the deep water in the centre of the Creek, and you will pass a couple of heavy moorings and an unlit green conical buoy together with a matching unlit red can buoy.

Sharfleet Creek branches off to the West just after the green buoy where it performs a convoluted upside down U and then carries on westwards, finally petering out and drying.

Stangate Creek continues southwards to Slaughterhouse Point, where it splits into two, Twinney Creek to the West and The Shade to the East. Both of these shortly peter out and dry, with The Shade terminating in an area known as Bedlams Bottom ! An offshoot of Twinney Creek, Halstow Creek leads to the village of Lower Halstow, but the whole area totally dries out. If at anchor in this area a dinghy mission could be mounted to the village which has a pub and a shop, and a yacht club.

Anchorage is available anywhere within the areas described above... possible spots are shown on the chart. It is very unlikely anything large will be moving up and down the creeks, but it's still probably a good idea to keep the centre of the channel clear if you can. The place is busy with small craft yachts at weekends.

Half Acre Creek is entered from the main river by leaving the number 16 red can Bishop Buoy to starboard and heading the generally South West direction. It is deep and wide, but at high water the whole area is completely covered, thus it is not popular for anchoring (although there's nothing to stop you if you want to).

It does however lead to a couple of useful (but drying) facilities, a boatyard at the head of Otterham Creek and Mariners Farm boatyard at Rainham, lying just South of the curiously named Horrid Hill. I've looked at this protuberance many times and never been able to work out why it's quite so horrid....

.... Otterham Creek Boatyard has a Face Book page but there is no website

Mariners Farm offers drying moorings, and vast areas of storage ashore and DIY projects are welcome. It can really only be approached by boat close to HW. A link to their website is below:

Anyway Halfacre Creek leads south-westwards to the Otterham Fairway buoy, which is red and white (Mo(A)10s) and from here it splits three ways. The South going channel is Otterham Creek. This dries out but is marked clearly by red and green buoyage right up to Otterham Quay, where you will find a boatyard. Approach could be made one hour either side of high water.

The middle fork off is called Bartlett Creek, and is marked by three red buoys and eventually ends up taking you to Mariners Farm Boatyard, with the above-mentioned Horrid Hill well off on your starboard side. Approach could be made a couple of hours either side of high water.They are unlikely to have any casual moorings, but have plenty of shoreside storage for boats and projects. They do maintain a few drying moorings too.

The most northerly fork from this junction is the South Yantlet Creek. It is marked by red and white buoys and cuts round the back of Darnett Ness to rejoin the main Medway. It too dries out, but could be a useful shortcut for locals.

None of these creeks described are popular for anchoring even though they have water, because when the tide is in there is no shelter from the wind.

At one time small coasters used to use Bloors wharf, but no more.

Facilities

Apart from the two boatyards and one yacht club mentioned there is nothing in this area. Any kind of stocking up, fuelling or watering will need to be done further into the Medway, or alternatively at Queenborough in the Western Swale.

This is close by to Stangate Creek, and is covered in a separate article.

History

Dutch Raid on the Medway 1667.

The Raid on the Medway, sometimes called the Battle of Medway or the Battle of Chatham, was a successful Dutch attack on the largest English naval ships, laid up in the dockyards of their main naval base Chatham, that took place in June 1667 during the Second Anglo-Dutch War. The Dutch, under nominal command of Lieutenant-Admiral Michiel de Ruyter, bombarded and captured Sheerness, went up the River Thames to Gravesend, then up the River Medway to Chatham, where they burnt three capital ships and ten lesser naval vessels and towed away the Unity and the Royal Charles, pride and normal flagship of the English fleet. The raid led to a quick end to the war and a favourable peace for the Dutch. It is considered to be the greatest defeat in English naval history.

English king Charles II's active fleet had already been reduced to accommodate the restrictions of recent expenditure with the "big ships" remaining laid up, so the Dutch seized their opportunity well. They had had earlier plans for such an attack in 1666 after the Four Days Battle but were prevented from carrying them out by their defeat in the St James's Day Battle. The mastermind behind the plan was the leading Dutch politician Grand Pensionary Johan de Witt. His brother Cornelis de Witt accompanied the fleet to supervise. Peace negotiations were already in progress at Breda since March, but Charles tried to procrastinate the signing of peace, hoping to improve his position through secret French assistance, so De Witt thought it best to end the war quickly with a clear Dutch victory, which of course might lead to more favourable terms. Most Dutch flag officers had strong doubts about the feasibility of an attack, fearing the treacherous shoals in the Thames estuary, but they obeyed orders nevertheless. The Dutch made use of two defected English pilots, one a dissenter (a "fanatic") named Robert Holland, the other a smuggler having fled English justice.

The Dutch approach

On 17 May the squadron of the Admiralty of Rotterdam sailed to Texel to join those of Amsterdam and the Northern Quarter. Hearing that the squadron of Frisia wasn't yet ready because of recruiting problems (impressment being forbidden in the Republic), he left for the Schooneveld off the Dutch coast to join the squadron of Zealand, that however suffered from similar problems. De Ruyter then departed for the Thames on 4 June (Old Style) with 62 frigates or ships-of-the-line, about fifteen lighter ships and twelve fireships, when the wind turned to the east. The fleet was reorganised into three squadrons: the first was commanded by De Ruyter himself, with as Vice-Admiral Johan de Liefde and Rear-Admiral Jan Jansse van Nes; the second was commanded by Lieutenant-Admiral Aert Jansse van Nes with as Vice-Admiral Enno Doedes Star and Rear-Admiral Willem van der Zaan; the third was commanded by Lieutenant-Admiral Baron Willem Joseph van Ghent with Lieutenant-Admiral Jan van Meppel in subcommand and as Vice-Admirals Isaac Sweers and Volckert Schram and as Rear-Admirals David Vlugh and Jan Gideonsz Verburgh.[1] The third squadron thus effectively had a second set of commanders; this was done to use these as flag officers of a special frigate landing force, to be formed on arrival and to be headed by Colonel and Lieutenant-Admiral Van Ghent, on the frigate Agatha. Baron Van Ghent was in fact the real commander of the expedition and had done all the operational planning, as he had been the former commander of the Dutch Marine Corps, the first in history to be specialised in amphibious operations, that now was headed by the Englishman Colonel Thomas Dolman.

Map showing the events

On 6 June a fog bank was blown away and revealed the Dutch task force, sailing into the mouth of the Thames. On 7 June Cornelis de Witt revealed his secret instructions from the States-General, written on 20 May, in the presence of all commanders. There were so many objections, while De Ruyter's only substantial contribution to the discussion was "bevelen zijn bevelen "("orders are orders"), that Cornelis, after retiring to his cabin late in the night, wrote in his daily report he didn't feel at all sure that he would be obeyed. The next day it transpired however that most officers were in for a bit of adventure; they had just given their professional opinion for the record so they could blame the politicians should the whole enterprise end in disaster. That day an attempt was made to capture a fleet of twenty English merchantmen seen higher up the Thames in the direction of London, but this failed as these fled to the west, beyond Gravesend.

The attack caught the English unawares. No serious preparations had been made for such an eventuality, although there had been ample warning from the extensive English spy network. Most frigates were assembled in squadrons at Harwich and in Scotland, leaving the London area to be protected by only a small number of active ships, most of them prizes taken earlier in the war from the Dutch. As a further economy measure on 24 March the Duke of York had ordered to discharge most of the crews of the prize vessels, leaving only three guard ships at the Medway; in compensation the crew of one of them, the frigate Unity (former Dutch Eendracht, the first ship to be captured in 1665, from the privateer Cornelis Evertsen the Youngest) was raised from forty to sixty; also the number of fireships was increased from one to three. Additionally thirty large sloops were to be prepared to row any ship to safety in case of an emergency. Sir William Coventry declared that a Dutch landing near London was very unlikely; at most the Dutch, to bolster their morale, would launch a token attack at some medium sized and exposed target like Harwich, which place therefore had been strongly fortified in the spring. There was no clear line of command with most responsible authorities giving hasty orders without bothering to coordinate them first. As a result there was much confusion. Charles didn't take matters into his own hands, deferring mostly to the opinion of others. English morale was low. Not having been paid for months or even years, most sailors and soldiers were less than enthusiastic to risk their lives. England had only a small army and the few available units were dispersed as Dutch intentions were unclear. This explains why no effective countermeasures were taken though it took the Dutch about five days to reach Chatham, slowly manoeuvring through the shoals, leaving the heavier vessels behind as a covering force. They could only advance in jumps when the tide was favourable.

After raising the alarm on 6 June at Chatham Dockyard, Commissioner Peter Pett seems not to have taken any further action until 9 June when, late in the afternoon, a fleet of about thirty Dutch ships were sighted in the Thames off Sheerness. At this point the Commissioner immediately sought assistance from the Admiralty sending a pessimistic message to the Navy Board, lamenting the absence of Navy senior officials whose help and advice he believed he needed. The thirty ships were those of Van Ghent's squadron of frigates. The Dutch fleet carried about a thousand marines and landing parties were dispatched on Canvey Island in Essex and opposite on the Kent side at Sheerness. These men had strict orders by Cornelis de Witt not to plunder, as the Dutch wanted to shame the English whose troops had sacked Terschelling during Holmes's Bonfire in August 1666. Nevertheless the crew of captain Jan van Brakel couldn't control themselves. They were driven off by English militia and under threat of severe punishment when returning to the Dutch fleet. Van Brakel offered to lead the attack the next day to avoid the penalty.

The king ordered the Earl of Oxford on 8 June to mobilise the militia of all counties around London; also all available barges should be used to lay a ship bridge across the Lower Thames, so that the English cavalry could quickly switch positions from one bank to the other. Sir Edward Spragge, the famous Vice-Admiral, learned on 9 June that a Dutch raiding party had come ashore on the Isle of Grain (a peninsula where the river Medway in Kent, meets the River Thames). Musketeers from the Sheerness garrison opposite were sent to investigate.

The King only in the afternoon of 10 June instructed Admiral George Monck, Duke of Albemarle to go to Chatham to take charge of matters and ordered Admiral Prince Rupert to organise the defences at Woolwich a full three days later. Albermarle first went to Gravesend where he noted to his dismay that there and at Tilbury only a few guns were present, too few to halt a possible Dutch advance upon the Thames. To prevent such a disaster, he ordered all available artillery from the capital to be positioned at Gravesend. On 11 June (Old Style) and New Style dates|Old Style]] he went to Chatham, expecting the place to be well prepared for an attack. Two members of the Navy Board, Sir John Mennes and Lord Henry Brouncker, had already travelled there on the same day. When Albemarle arrived, however, he found only twelve of the eight hundred dockyard men expected and these in a state of panic; of the thirty sloops only ten were present, the other twenty having been used to bring the personal possessions of several officials to safety, such as the ship models of Pett. No munition or powder was available and the chain that blocked the Medway had not been protected by batteries. He immediately ordered to move the artillery from Gravesend to Chatham, which would take a day to effect.

The Dutch fleet arrived at the Isle of Sheppey on 10 June, and launched an attack on the incomplete Sheerness Fort. Captain Jan van Brakel in Vrede, followed by two other men-of-war, sailed as close to the fort as possible to engage it with cannon fire. Sir Edward Spragge was in command of the ships at anchor in the Medway and those off Sheerness, but the only ship able to defend against the Dutch was the frigate Unity which was stationed off the fort.

The Unity was supported by a number of ketches and fireships at Garrison Point, and by the fort where sixteen guns had been hastily placed. The Unity fired one broadside, but then, when attacked by a Dutch fireship, she withdrew up the Medway, followed by the English fireships and ketches. The Dutch fired on on the fort; two men were hit. It then transpired that no surgeon was available and most soldiers of the Scottish garrison deserted. Seven remained but their position became untenable when some 800 Dutch marines landed about a mile away. With Sheerness thus lost, its guns being captured by the Dutch and the building blown up, Spragge sailed up river on his yacht the Henrietta, for Chatham. In that place now many officers were assembled: Spragge himself, the next day also Monck and several men of the admiralty board. All gave orders countermanding those of the others so that utter confusion reigned.

As his artillery would not arrive soon, Monck on the 11th ordered a squadron of cavalry and a company of soldiers to reinforce Upnor Castle. River defences were hastily improvised with blockships sunk, and the chain across the river was guarded by light batteries. Pett proposed that several big and smaller ships be sunk to block the Musselbank channel in front of the chain. This way the large HMS Golden Phoenix and HMS House of Sweden (the former VOC - ships Gulden Phenix and Huis van Swieten) and HMS Welcome and HMS Leicester were lost and the smaller Constant John, Unicorn and John and Sarah; when this was shown by Spragge, personally sounding the depth of a second channel despite the assurances by Pett, to be insufficient, they were joined by the Barbados Merchant, Dolphin, Edward and Eve, Hind and Fortune. To do so the men first intended for the warships to be protected were used, so the most valuable ships were basically without crews. These blockships were placed in a rather easterly position, on the line Upchurch - Stoke and could not be covered by fire. Monck then decided also to sink off ships in Upnor Reach near Upnor Castle, presenting another barrier to the Dutch should they break through the chain at Gillingham. The defensive chain placed across the river had at its lowest point been lying practically nine feet (about three metres) under the waterline between its stages owing to its weight, so it was still possible for light ships to pass it. It was tried to raise it by placing stages under it closer to the shore.

The positions of Charles V and Matthias (former Dutch merchantmen Carolus Quintus and Geldersche Ruyter), just above the chain were adjusted to enable them to bring their broadsides to bear upon it. Monmouth was also moored above the chain, positioned so that she could bring her guns to bear on the space between Charles V and Matthias. The frigate Marmaduke and the Norway Merchant were sunk off above the chain; the large Sancta Maria (former VOC-ship Slot van Honingen of 70 cannon) foundered while being moved for the same purpose. Pett also informed Monck that the Royal Charles had to be moved upriver. He had been ordered by the Duke of York on 27 March to do this, but as yet hadn't complied. Monck at first refused to make available some of his small number of sloops, as they were needed to move supplies; when he at last found the captain of the Matthias willing to assist, Pett answered that it was too late as he was busy sinking off the blockships and there was no pilot to be found daring to take such a risk anyway. Meanwhile the first Dutch frigates to arrive had already begun to move away the Edward and Eve, clearing a channel by nightfall.

Van Ghent's squadron now advanced up the Medway on 12 June attacking the English defences at the chain. First Unity was taken by Van Brakel by assault. Then the fireship Pro Patria under commander Jan Daniëlsz van Rijn broke through the chain (or sailed over it according to some historians, distrusting the more spectacular traditional version of events), the stages of which were soon after destroyed by Dutch engineers commanded by Rear-Admiral David Vlugh. It then destroyed the Matthias by fire. The fireships Catharina and Schiedam attacked the Charles V; the Catharina under commander Hendrik Hendriksz was sunk by the shore batteries but the Schiedam under commander Gerrit Andriesz Mak successfully set the Charles V alight; the crew was captured by Van Brakel. Royal Charles, with only thirty cannon aboard and abandoned by its skeleton crew when it saw the Matthias burn, was then captured by the Irishman Thomas Tobiasz, the flagcaptain of Vice-Admiral Johan de Liefde, and carried off to the Netherlands despite an unfavourable tide. This was made possible by lowering its draught by bringing it into a slight tilt. The jack was struck while a trumpeter played "Joan's placket is torn". Only the Monmouth escaped. Seeing the disaster Monck ordered all sixteen remaining warships further up to be sunk off to prevent them from being captured, making for a total of about thirty ships deliberately sunk by the English themselves. As Andrew Marvell satirised:

Of all our navy none should now survive,

But that the ships themselves were taught to dive

The following day, 13 June, the whole of the Thames side as far up as London was in a panic — some spread the rumour that the Dutch were in the process of transporting a French army from Dunkirk for a full-scale invasion — and many wealthy citizens fled the city, taking their most valuable possessions with them. The Dutch continued their advance into the Chatham docks with the fireships Delft, Rotterdam, Draak, Wapen van Londen, Gouden Appel and Princess under English fire from Upnor Castle and from three shore batteries. A number of Dutch frigates suppressed the English fire, themselves suffering about forty casualties in dead and wounded. Three of the finest and heaviest vessels in the navy, already sunk to prevent capture, now perished by fire: first the Loyal London, set alight by the Rotterdam under commander Cornelis Jacobsz van der Hoeven; then the Royal James and finally the Royal Oak, that withstood attempts by two fireships but was burnt by a third. The English crews abandoned their half-flooded ships, mostly without a fight, a notable exception being army captain Archibald Douglas, of the Scot Foots, who refused to personally abandon the Oak and perished in the flames. The Monmouth again escaped. The raid thus cost the English four of their remaining eight ships with more than 75 cannon. Three of the four largest "big ships" of the navy were lost. The remaining "big ship", Royal Sovereign (the former HMS Sovereign of the Seas rebuilt as a two-decker), was preserved due to its being at Portsmouth at the time. De Ruyter now joined Van Ghent's squadron in person.

The Dutch withdraw

As he feared a stiffening English resistance, Cornelis de Witt on 14 June decided to forgo a further penetration and withdraw, towing the Royal Charles along as a war trophy; the Unity also was removed with a prize crew. This decision saved the sunk off capital ships HMS Royal Katherine, HMS Unicorn, HMS Victory and HMS St George. However Dutch demolition teams that day rowed on boats to any ship they could reach to burn it down as much as they could, thus ensuring their reward money. One boat even reentered the docks to make sure nothing was left of the Oak, James and London; another, by accident or malicious intent, burnt the Slot van Honingen, though it had been intended to salvage this precious merchantman. Now the English villages were plundered - by their own troops. The Dutch fleet, after celebrating by collectively thanking God for "a great victory in a just war in self-defence" tried to repeat its success by attacking several other ports on the English east coast but was repelled each time. On 27 June an attempt to enter the Thames beyond Gravesend was called off when it became known that the river was blocked by blockships and five fireships awaited the Dutch attack. On 2 July a Dutch marine force landed at Woodbridge near Harwich and successfully prevented Landguard Fort from being reinforced but a direct assault on the fort by 1500 marines was beaten off by the garrison. On 3 July an attack on Osleybay failed. On 21 July Julian calendar peace was signed.

But still, Samuel Pepys notes in his diary on 17 July 1667: "The Dutch fleete are in great squadrons everywhere still about Harwich, and were lately at Portsmouth; and the last letters say at Plymouth, and now gone to Dartmouth to destroy our Streights' fleete lately got in thither; but God knows whether they can do it any hurt, or no, but it was pretty news come the other day so fast, of the Dutch fleets being in so many places, that Sir W. Batten at table cried, By God, says he, I think the Devil shits Dutchmen."

And on 29 July 1667: "Thus in all things, in wisdom, courage, force, knowledge of our own streams, and success, the Dutch have the best of us, and do end the war with victory on their side".

Aftermath

Wharf official John Norman estimated the damage caused by the raid at about £20,000, apart from the replacement costs of the four lost capital ships; the total loss of the Royal Navy must have been close to £200,000. Pett was made a scapegoat, bailed at £5,000 and deprived of his office whilst those who had ignored his earlier warnings quietly escaped any blame. The Royal James, Oak and Loyal London were in the end salvaged and rebuilt, but with great cost; when London refused to share in it, Charles had the name of the latter ship changed into a simple London. For a few years the Dutch fleet was the strongest in the world, but around 1670 a new building programme had restored the English Navy to its former power.

The Raid on the Medway was a serious blow to the reputation of the English crown. Charles felt personally offended by the fact the Dutch had attacked while he had laid up his fleet and peace negotiations were ongoing, conveniently forgetting he had not negotiated in good faith. His resentment was one of the causes of the Third Anglo-Dutch War as it made him enter into the secret Treaty of Dover with Louis XIV of France. In the 19th century, nationalistic British writers expanded on this theme by suggesting it were the Dutch who had sued for peace after their defeats in 1666 — although in fact these had made them if anything more belligerent — and that only by treacherously attacking the British nevertheless they had been able to gain a victory; a typical example is When London burned written by the novellist G. A. Henty in 1895.

Total losses for the Dutch were eight spent fireships and about fifty casualties. In the Republic the populace was jubilant after the victory; many festivities were held, repeated when the fleet returned in October, the various admirals being hailed as heroes. They were rewarded by a flood of eulogies and given honorary golden chains and pensions by the States-General and the lesser States of the Provinces; De Ruyter, Cornelis de Witt and Van Ghent were honoured by precious enamelled golden chalices, depicting the events. Cornelis de Witt had a large "Sea Triumph" painted, with himself as the main subject, which was displayed in the townhall of Dort. This triumphalism by De Witt's States faction caused resentment with the rivalling Orangist faction; when the States regime lost its power during the rampjaar 1672, Cornelis's head would be ceremoniously carved out from the painting, after Charles had for some years insisted the picture would be removed.

Royal Charles, its draught too deep to be of use in the shallow Dutch waters, was permanently drydocked near Hellevoetsluis as a tourist attraction, with day trips being organised for large parties, often of foreign state guests; after vehement protests by Charles that this insulted his honour, the official visits were ended and Royal Charles was eventually scrapped in 1672; but in the cellar of the Rijksmuseum of Amsterdam part of her transom, bearing the coat of arms with the Lion and Unicorn and the inscription Dieu et mon droit is still on display.

The text on this HISTORY page is covered by the following licence

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Text_of_the_GNU_Free_Documentation_License

Eating, Drinking & Entertainment

Again in the area described there is nowhere for you to nip ashore for a quick pint and a bite to eat.(With the possible exception of an dinghy mission into Lower Halstow, from the lower end of Stangate Creek.)

Links

Interesting article about the wreck of the Richard Montgomery, you'll pass this on the way into the Medway if coming from the East:

|

Your Ratings & Comments